| 龚鹏程x戴维德·乔塞利特|媒体扩张宛如病菌 | 您所在的位置:网站首页 › modernity和modernism什么区别 › 龚鹏程x戴维德·乔塞利特|媒体扩张宛如病菌 |

龚鹏程x戴维德·乔塞利特|媒体扩张宛如病菌

|

在《遗产与债务》一书中,我提到了在1990年代进入国际艺术市场和博物馆展览时,遗产的复兴特别有效地使中国和俄罗斯的艺术为全球观众所理解。此外,我还以澳大利亚原住民为背景,讨论了绘画如何成为维护土地权利的工具,因为原住民绘画除了拥有吸引西方人的抽象美学之外,其中关于土地的描绘也成为了让法院可以接受的土地其实一直是被原住民占领的一项证据。 Colloquially, the term heritage denotes a "fixed" or conservative tradition--such as the revived interest in English country houses in the Anglophone world during the 1980s. But in Heritage and Debt I define heritage as any inherited cultural tradition, and as such, I argue that local, national, or regional forms of heritage may serve as powerful resources for animating contemporary culture across the globe. From this perspective, twentieth-century European avant-gardes constitute only one regional tradition among many, consisting of an array of practices committed to innovating new forms, often corresponding to new utopian ways of life. But the Western hegemony over art-historical and museum infrastructure during the twentieth century led to the avant-garde's being installed as a universal norm for modern culture, rather than a single variant of it. Consequently, Western historians and theorists have tended to regard non-Western modernity as developmentally inferior to Western models, thus establishing the deeply engrained assumption that a people, nation, or region must necessarily be desirous of attaining Western modernity in order to become modern at all. From this attitude the second term of my title emerges--the ideological conviction that the World owes a debt to the West for its "gift" of modernity. In the realm of form, such indebtedness is indicated when non-Western contemporary art is dismissed as derivative of Western norms. However, if we regard the Western avant-garde tradition as a particular European form of heritage, which was imposed upon the rest of the world through imperialism and cultural neo-imperialism, then the "debt" to the West is put paid (or more accurately, rendered merely ideological) in the face of the many other ways that modernity arose out of myriad other types of heritage. In Heritage and Debt, I note that the reanimation of heritage was particularly effective in making both Chinese and Russian art intelligible to global audiences when it entered international art markets and museum exhibitions in the 1990s. Moreover, I discuss how in the Aboriginal Australian case, painting became a tool for asserting land rights because, beyond the abstract aesthetics that appealed to Western eyes, Aboriginal painting stored knowledge about the land that courts accepted as proof of its continuous occupation by Aboriginal peoples. 龚鹏程教授:在您的文章《病毒的隐喻》中,您讨论了媒体中虚假信息和信息授权的危机。请问艺术家和艺术评论家是如何应对这场危机的?是否有可以借鉴的历史先例? 戴维德·乔塞利特教授:二十世纪西方媒体从广播到电视到互联网这段历史,其实是一个关于多种新的交流空间的突然出现并相继进行商业扩张的故事。 所有这些技术都起源于军事研究,但当他们作为公共设施被使用时却缺少了一个明确的目的或效用。在这种情况下,随着这些新“网络和媒体”的受众增加,信息交流也相继商业化。“网络和媒体”是一种以广告盈利为基础的架构方式(除非政府为“网络和媒体”提供全额资金,在这种情况下“网络和媒体”很有容易受到审查)。 正如我在2007年出版的《反馈:反对民主的电视》一书中所展示的二十世纪中叶的媒体生态系统,它包含了有线商业电视、视频艺术和视频能动性,而“网络”将其观众的注意力作为商品卖给广告商。此外,无论是情景喜剧还是连续的视频艺术表演,每种类型的信息都假设拥有特定的观众。相反,观众也会对这些信息设限,比如大众不会观看布鲁斯·瑙曼(一位美国概念艺术家)的视频,真人秀也不会在博物馆上演。所以,当我们说到“信息”的时候,我们通常指的是一群特定或合适的观众通过其注意力所授权的信息。 概念艺术是一种描绘信息、授权和观众三方关系的美学实例,艺术作品由艺术家授权作为一种信息形式,而非必须要由他们制作。艺术已经可以断言这三个要素的不可分割性。 但是,我不认为所谓的揭露意识形态关系的颠覆性政治本身在政治上是有效的。汉娜·阿伦特曾提出说政治包含了让新事物出现,这也是艺术可以做的。艺术和政治一样,是一个外部空间,但是它们基础架构和权力的性质显然大相径庭。一个人如果只是想象生活该是怎样的,那该如何创作出一个真正的外部空间?虽然这是很困难的,但是艺术仍然拥有实现它们的潜力。 The history of twentieth century media in the West, from radio to television to the Internet is a story of the sudden appearance of new spaces of communication, and their successive commercial enclosure. All these technologies had their origins in military research and when they emerged as public, none had a clear purpose or utility. In each case, as these new networks accrued audiences, the exchange of information was successively commodified. Networks are a form of infrastructure that is paid for by advertising (unless a government funds them fully, in which case they are vulnerable to censorship). As I showed in my 2007 book, Feedback: Television Against Democracy, which charted a mid-twentieth century media ecology encompassing cable television commercial television, video art and video activism, networks produce audiences as commodities whose attention they sell to advertisers. Moreover, each genre of information, whether a situation comedy, or a durational video art performance, presumes an audience with a certain profile. Conversely, audiences create limits on what any genre can do. A mass audience will not watch a Bruce Nauman video, and reality television will not be exhibited in a museum. Consequently, when we say "information," we are always also implying a particular audience--or niche--that authorizes that information through its attention. Conceptual art, in which art works are authorized by artists as a form of information, rather than necessarily produced by them, is an aesthetic instantiation of the tripartite relationship between information, authorization, and audience. Asserting the inextricability of these three elements is already a contribution that art can make. However, I don't believe that a so-called subversive politics of unveiling or uncovering ideological relationships is in itself politically efficacious. Politics, as Hannah Arendt argued, consists of making something new appear--and this, too, is what art can do. Art, like politics, is a space of appearance, but the nature of its infrastructure and its power is obviously quite different. How can one make a genuine space of appearance, where life can be imagined otherwise? This is difficult, but this is what art has the potential to achieve. 龚鹏程教授:在2015年时,您在慕尼黑布兰德霍斯特博物馆协办了展览《绘画2.0:信息时代的表达》,这个主题即使在2022年也非常有趣。请问这个展览的侧重点是什么?艺术家如何使用新媒体来表达自己?自上次展览以来,出现了哪些新的发展? 戴维德·乔塞利特教授:创办《绘画2.0》的前提之一是,绘画,作为一种非常古老甚至保守的媒介,可以捕捉到从电视到互联网这种电子媒体流的情感品质。 它能够同时在画布或其它媒介这种空间中捕获持续的图像流,而这也是我对于绘画感兴趣的方面之一。绘画可以通过抓住一些短暂的事务将时间转换为空间,就像在互联网上找到的图像一样,并以让我们研究它以及它隐含的轨迹的方式去展示时间的流逝。我有时会把它称为绘画展示“图像行为”的能力。 《绘画2.0》分为三个部分,包括波普艺术,新现实主义对于现实的挪用和当代艺术作品,旨在为二战后欧洲和北美的绘画建立一种以绘画与大众媒体关系为基础的新的标准。 我目前正在策划一个新的以绘画为导向的项目,可能会以短篇书籍的方式呈现而非展览。我有兴趣从去形象化的角度重新阅读现代绘画的历史,而不是像人们经常说的那样作为一个从具象到抽象的演变进行研究。 在文艺复兴以来的西方绘画传统中,通常都以创造一个焦点动作及其各种分支,包括一系列不同的情感反应,来和谐地表达人物的构成。换言之,16-19世纪中叶的欧洲绘画就已经确立了对神圣和世俗生活形象的想象。但是从爱德华·马奈时代开始,这种形象在现代绘画中就只能因许多可争论的原因被去形象化。在我看来,这种去形象化模型可以一箭双雕。首先,即使是在艺术史文学中因偏爱通过抽象来讲述现代主义的历史而很大程度上被掩盖的现实主义或具象绘画,也可以被广泛地包含于20世纪的艺术中;其次,去形象化模型使我们能够将现代主义理解为对人类本质的一种反思——在与西方现代性相关的工业化、城市化和消费的条件下,现代主义是如何变形、重新定形或无形象的。 One of the premises of "Painting 2.0" was that painting, as a very old, and even conservative medium, could capture something about the affective qualities of electronic media flows, ranging from television to the Internet. One of my interests in painting is that it can arrest durational streams of images in a space--the canvas or other support--of simultaneity. Painting can turn time into space, by seizing upon something ephemeral such as an image found on the Internet and present it in such a way that we can examine it, and its implied trajectories. I sometimes refer to this as painting's capacity to demonstrate the "behavior of images." "Painting 2.0," which was divided into three parts, included Pop art, appropriation, and very contemporary works. It ambitiously aimed to create a new canonical view of post-World War II painting in Europe and North America, that is founded in painting's relationship to mass media. I am currently contemplating a new painting-oriented project, which will probably result in a short book rather than an exhibition. I'm interested in re-reading the history of modern painting in terms of disfiguration rather than as an evolution from figuration toward abstraction, as it is still often told. In the Western tradition of painting since the Renaissance, the composition of figures was articulated harmonically, in order to create a focal action and its various ramifications, usually including an array of different sentimental or affective reactions. In other words, European painting of the 16th-mid-19th centuries established a figural imagination of sacred and secular life. For various reasons that we could debate, such figuration yielded to disfiguration in modern painting, certainly from the time of Edouard Manet onward. As I see it, the virtue of this model of disfiguration is twofold. First, it allows us to encompass a broad range of realist or figurative painting within 20th century art that has been largely overshadowed in the art-historical literature through the preference for telling modernism's history through abstraction; and secondly, the model of disfiguration allows us to understand modernism as a reflection on the nature of the human--how it is dis- or re- or un-figured under conditions of industrialization, urbanization, and consumption associated with Western modernity. 龚鹏程教授:您认为亚洲艺术的哪些现代趋势感兴趣,为什么? 戴维德·乔塞利特教授:我只能作为一个局外人来了解亚洲艺术,对当代作品产生的传统缺乏深刻的理解。 虽然我以前经常在亚洲旅行,但自新冠疫情爆发以来,我就没有去过亚洲,因此很难在概念差异和物理差异较大的情况下理解亚洲艺术的新发展。 在我所了解到的关于中国艺术中,最重要观点之一就是来自于张颂仁和高世明于2015年主编的精彩集锦《三个艺术世界:中国现代史中的一百件艺术物》。它展示了中国的现代性沿着三条有时相互交织,有时相互矛盾的道路发展:水墨艺术,社会主义下的现实主义,以及前卫艺术。其中有一些当代艺术形式比其它更容易被全球所接受,但要了解中国现当代艺术的历史,就必须考虑到这三个平行的艺术世界。鉴于我渴望将现代和当代艺术理解为源于多个起点(即多种遗产资源),这项工作对我来说非常鼓舞人心。 I can only know Asian art as an outsider, who lacks a deep understanding of the traditions from which contemporary work emerges. Though I have often traveled in Asia, I have not done so since the beginning of the pandemic, so it is hard to understand new developments from a great conceptual and physical distance. Among the most important perspectives I've encountered on Chinese art is the fantastic catalogue edited by Chang Tsong-Zung and Gao Shiming in 2015, 3 Parallel Art Worlds: 100 Things from Chinese Modern History which indicates that modernity in China developed along three sometimes interweaving, and sometimes contradictory pathways: Ink Art, Socialist Realism, and avant-garde art. Some of these contemporary forms are more accessible to global audiences than others, but to understand the history of Chinese modern and contemporary art these three parallel art worlds must be accounted for. Given my desire to understand modern and contemporary art as arising from multiple starting points (i.e., multiple resources of heritage), this work has been highly inspirational for me.

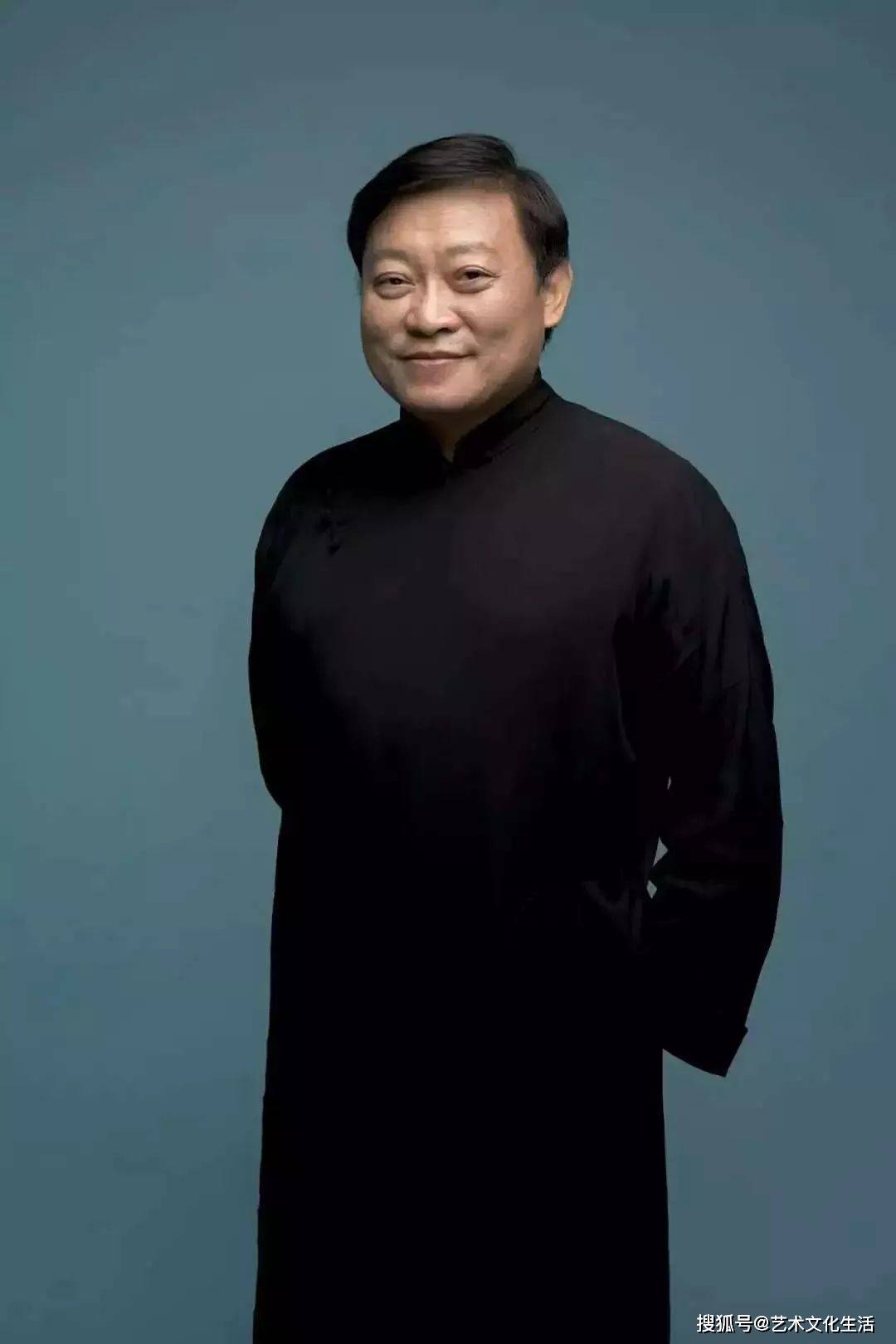

龚鹏程,1956年生于台北,台湾师范大学博士,当代著名学者和思想家。著作已出版一百五十多本。 办有大学、出版社、杂志社、书院等,并规划城市建设、主题园区等多处。讲学于世界各地。并在北京、上海、杭州、台北、巴黎、日本、澳门等地举办过书法展。现为美国龚鹏程基金会主席。返回搜狐,查看更多 |

【本文地址】